cleve higgins & fred burrill

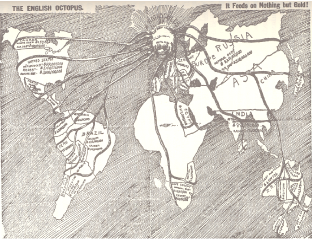

Over the last decade, the violent and destructive practices of Canadian mining companies operating abroad have become a major concern for environmental and international solidarity activists in Canada. And for good reason: Canada-based corporations are a dominant force in the world’s mineral extraction industry, leaving a trail of environmental and social destruction (and bodies) across neoliberalized economies in Africa, in Asia and the Pacific, and in Latin America.

We first came to this issue several years ago as solidarity activists working with the Frente Amplio Opositor (FAO, or Broad Opposition Front) of San Luis de Potosi, Mexico, where the Canadian company Metallica Resources (and now New Gold) first began its attempt to operate an illegal gold mine in the small historic community of Cerro de San Pedro following the neoliberalization of Mexico’s mineral laws through NAFTA. Through this campaign we organized a series of demonstrations, theatrical actions, and educational activities in concert with the efforts of the FAO in Mexico, making links with the many other organizations and affected communities mobilizing against Canadian international mining practices from Montreal.

In doing so, though, and in becoming more involved in indigenous solidarity work in Montreal, we started to question some assumptions in the movement: principally, that Canadian mining’s devastating global impact was an aberration in an otherwise benevolent historical and contemporary political culture, correctable through sensible legislative reforms. We began trying to make links between the actions of Canadian companies abroad and the historical and ongoing theft of indigenous lands by the Canadian State, looking at the relationship between the development of Canadian capitalism and colonial structures here in the northern part of Turtle Island. This paper is a first step in the process of making these connections. We argue here that Canada’s dominant role in the international mining industry is actually a case of this country’s internal colonialism turning outward to do its worst in the rest of the world – that Canada’s growth as a political and economic entity needs to be understood as part of a larger story of the development of global capitalism and imperial competition for precious metals, predicated on an ever-increasing consumption of indigenous territory. In what follows we look at the (historical) imperial context of precious metals extraction in the land now known as Canada, and elaborate an analysis of the development of mining capital and Canadian financial structures. We hope that this contribution can lead to more discussion and analysis connecting anti-mining solidarity work with communities abroad to the ongoing struggle against colonialism here.

In doing so, though, and in becoming more involved in indigenous solidarity work in Montreal, we started to question some assumptions in the movement: principally, that Canadian mining’s devastating global impact was an aberration in an otherwise benevolent historical and contemporary political culture, correctable through sensible legislative reforms. We began trying to make links between the actions of Canadian companies abroad and the historical and ongoing theft of indigenous lands by the Canadian State, looking at the relationship between the development of Canadian capitalism and colonial structures here in the northern part of Turtle Island. This paper is a first step in the process of making these connections. We argue here that Canada’s dominant role in the international mining industry is actually a case of this country’s internal colonialism turning outward to do its worst in the rest of the world – that Canada’s growth as a political and economic entity needs to be understood as part of a larger story of the development of global capitalism and imperial competition for precious metals, predicated on an ever-increasing consumption of indigenous territory. In what follows we look at the (historical) imperial context of precious metals extraction in the land now known as Canada, and elaborate an analysis of the development of mining capital and Canadian financial structures. We hope that this contribution can lead to more discussion and analysis connecting anti-mining solidarity work with communities abroad to the ongoing struggle against colonialism here.

the early imperial quest for precious metals

Political economist Harold Innis (no radical thinker) wrote in 1941 that the “discovery of America by Europeans was a result of the search for precious metals, and the character of its occupation was profoundly influenced by their exploitation.”1 The whole dominant narrative of the European ‘discovery’ of Canada, then, with its adventurous ‘coureurs de bois’, plentiful stocks of fish, and peaceful yet backward natives, is complicated when we pay attention to the historical context of a brutal and global European proto-capitalist competition for gold and silver.

The mid-fifteenth century rise of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East frustrated the Crusading European powers at an historical moment in which their economies required gold and silver in order to finance expanding militaries and a growing dependence on Eastern luxury goods (spices, silk, etc.), propelling Portugal down the African coast and Spain (with Italian capital) across the Atlantic to Latin America in a “world-wide movement to encircle Islam and seize control of its sources of wealth.” The genocidal conquest of the Americas that followed resulted in the forceable extraction of unprecedented amounts of gold and silver, giving Spain a monopoly over the world’s supply of precious metals.2

Lured by the prospect of unlimited wealth, and in need of financial liquidity for military purposes, the English and French were not far behind. Both colonial powers chased visions of finding gold such as the Spanish encountered in Mexico and Peru, but ultimately precious metals were to shape the early colonization of Turtle Island in a more indirect fashion. The European economic system of the sixteenth century, known as “bullionism,” dictated that a state’s wealth depended on the amount of precious metals in its treasury: states lacking these commodities were forced to specialize in products that could be traded for gold and silver – like fish, for instance, or fur. As a more complex form of mercantilism (an economic system in which states as coherent economic units pursue positive balances of trade – exporting more than importing – with other states) developed into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there coalesced a whole system of inter-colonial competition between the English and the French in present-day eastern Canada to secure access to

“raw materials for processing into commodities suitable for export to third parties in return for gold and silver.”3 These resources, of course, came from colonized land – the total genocide of the Beothuk people in present-day Newfoundland is perhaps the most shocking by-product of this early gold-oriented imperialism, but the ongoing fur-fish-precious metals axis brought a series of wars, treaties, and dispossessions that continue to shape the political-social geography of indigenous-settler relations in this part of Canada today.

the gold rush: property was theft

The nineteenth century brought about a fundamental shift in the ways in which precious metals figured into global capitalism. Classical liberal thought was becoming hegemonic in a financial system dominated by the wealth and military might of Britain, with paper money circulated freely and pegged to the value of gold. In a new historical phase of imperialism, Britain exchanged political control over many of its colonial interests for economic overlordship through the London capital exchange.4 As more and more countries were forced to align with this international ‘gold standard’, the demand for – and thus the price of – gold skyrocketed. And, as economic historian R.T. Naylor writes, the world (and especially British colonies) experienced an “acute gold fever that sparked rushes to the interior of old continents and frantic exploration of new territories.”5 These gold rushes, based as they were on a massive, ‘boom and bust”’influx of European settlers into an area, brought about bloody and ultimately prefigurative conflicts that would restructure the legal, political and economic relations between colonizers and indigenous people in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, the U.S., and, most importantly for our analysis, Canada.

Beginning in the 1840s, gold rushes first hit in California and Australia. In the former case, the discovery of gold in 1848 accelerated the pace of U.S. imperialism (having just taken the territory from Mexico) to breakneck speed, instituting an unprecedented kind of “shock and awe” settlement pattern drawing on migrant and slave labour as indigenous peoples were driven out of their territories and subject to foreign diseases and wholesale slaughters committed by state and paramilitary forces. More than 100 000 indigenous people died in the first two years of the California gold rush, in what Professor Edward D. Castillo has referred to as “a massive orgy of theft and mass murder.”6 In Australia, a gold rush shepherded in by settlers fresh from California caused the settler population of the colony to double between 1851 and 1860, intensifying already rampant patterns of dispossession, disease and assimilation. When gold deposits were first discovered in mainland British Columbia in 1856, then, the northern part of Turtle Island was swept up in a worldwide process of “merciless, sometimes ethnocidal, wars to dislodge indigenous communities sitting atop loads of high-grade minerals.”7

Before the onset of the frantic search for precious metals, the social geography of this territory was characterized by complex relationships between diverse indigenous populations and the relatively recently-arrived European fur traders affiliated with the Hudson’s Bay Company. Gold mining, as historian Adele Perry writes, “profoundly shifted the trajectory of British Columbia’s colonial project.”8 As in many British colonial endeavours, state and capital worked closely together: when HBC’s original bid to extend its fur-trade monopoly to mineral extraction was unsuccessful, Company trader and Vancouver Island governor James Douglas declared that all mainland mineral rights belonged to the Crown. Evidence suggests the metropolitan government in London agreed, as it quickly claimed the whole of the mainland as its own, creating the colony of British Columbia in 1858 and placing Douglas at its head.9

B.C. was the first gold-rich territory in the world to experience an actual ‘staking rush’ (as opposed to the usual pell-mell scrambling of individual prospecting settlers), with new mining companies struggling to gain legal title to resource-laden land.10 The gold rush brought with it patterns of dependency, dispossession and disintegration of traditional ways of life for indigenous people, as well as occasioning the violent repression of several indigenous uprisings. But it was this all-out effort of the colonizers to claim land that would perhaps have the deepest impact on settler-indigenous relations. Instead of orchestrating treaties with aboriginal groups, as had been the colonial strategy on the other side of British North America in the previous century, the local government codified the intense process of dispossession into law with its 1859 Gold Fields Act. This piece of legislation, based on the mining law of fellow settler colonies Australia and New Zealand (which in turn had roots in the original California gold rush), introduced into Turtle Island the legal notion of ‘free entry’.

Based in the supposition that all mineral rights belong to the Crown, free entry systems operate on the assumption that mineral extraction is the most profitable of all possible uses for land – granting licensed mining companies the right to stake a claim anywhere at any time, regardless of either indigenous territorial claims or private property concerns. Other laws of this sort quickly spread across British North America – in Quebec and Ontario (then the United Province of Canada) first in 1864, and then in the respective codes enshrined after Confederation in tandem with the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century rushes for gold and silver in these provinces; and spreading eastward to Atlantic Canada (although only for a brief period in Nova Scotia). Free entry mining law continues to hold indigenous and non-indigenous communities alike across Canada in its grasp. In the words of West Coast Environmental Law scholar Karen Campbell, it “effectively comprises [all] other values in society.”12 We should not forget that it was born in the bloody conquest of indigenous lands in so-called British Columbia.

Finally, this rapid development of the West did much to spur on colonization and industrialization efforts in the rest of the country. British fears about American encroachment on the Pacific coast and the growth of a new settler market in British Columbia were important factors in the push to build a transcontinental railway, a process that brought about ethnocidal conflicts between the new Canadian government and Metis and other indigenous groups on the Prairies; that set the stage for the intensive production of silver, copper and other metals (and the discovery of gold) in Quebec and Ontario – with the concomitant land-grabbing legal framework and push to develop massive hydro-electric projects; that caused the exploitation and death of thousands of migrant (mostly Asian) labourers; and that played a foundational role in Britain’s political and economic push to bring about a Confederation of its colonies in North America. As excited boosters of Nova Scotia wrote in 1862, having just discovered the first traces of gold in their own province, “Gold, that magic power in suddenly creating new empires, is found at the same time in British Columbia, the western portal, and in Nova Scotia, the eastern outlet, of British America,” going on to confirm the multi-layered and imperial nature of the rise of the new country: “Who can doubt that Nova Scotia and British Columbia have a bright destiny before them, and that we may yet live to see them bound together in a chain of communication; along which the luxuries of Asia, passing on from ocean to ocean, will be borne upon their journey to the distant markets of the old world.”13 Contemporary Canada’s extraction industry is the standard bearer of a centuries-long process of gold-feverish land consumption by European powers.

the british brain

During our discussions of the mining industry and how to oppose it in the FAO, we have used an analogy of ‘the arms’ and ‘the brain’ to conceptualize the overall structure of the mining industry: the arms are the operations of mining companies on the ground all over the world, doing exploration and developing mines in the pursuit of mineral extraction. The brain is located in the northern financial centers, in the downtown offices of the investors, stock exchanges, and mining companies. In Canada this means Toronto and Vancouver, and to a lesser extent Montreal. This essay has thus far focused on the colonial destruction of the early arms of the mining industry on this continent. Less has been said regarding the ‘brain’ and this is in large part because earlier mining was less capital intensive, and therefore depended less on financial support from colonial centres.

Within the context of European colonial-capitalism there has been a general historical trend of mining becoming exponentially more capital intensive, profitable, and destructive.14 For the purposes of this essay the historical trend begins with the gold rushes in the 19th century, which were all extracting through placer mining. This method uses water to filter gold out of alluvial deposits left behind by ancient or existing streams. The easiest and most commonly known way of placer mining is to ‘pan’ for gold, which only requires a metal pan, and more advanced methods still only involved wooden sluice structures, and occasionally dams. These methods primarily takes place on the surface, are very labour intensive, and did not become more capital intensive until many years into the gold rush. Hence the large influxes of prospector-settlers who didn’t have much money to start with, but hoped to get rich anyway (and sometimes did).15

Stock exchanges did have a minor role in the placer gold rushes (such as the San Francisco exchange, and some not very successful investments from London). However, they became much more important during the late 19th and early 20th century, supporting the development of more capital intensive underground tunnel mining in the US, Canada, and throughout the British Empire.16 As mining has become more capital intensive and therefore dependent on centralized, elite/metropolitan financial support, there has come to be a more clearly defined ‘brain’ providing this support. For the tunnel mining of the late 19th and early 20th century this involved a combination of sources of financial capital: London for the British empire, New York for North America, and regional exchanges in most areas that had mining districts. This analysis will be looking at the increasingly important role of the financial brain(s) of the mining industry, and the role that they have had in relation to the precious metal mining of British settler colonies, and more recently in Canada.

Looking specifically at the US, which was the leading producer of mineral resources during the first half of the twentieth century, economists Paul David and Gavin Wright have argued that resource abundance is socially constructed, and not geographically determined:

The abundance of American resources did not derive primarily from geological endowment, we argue, but reflected the intensity of search; new technologies of extraction, refining and utilization; market development and transportation investments; and legal, institutional and political structures affecting all of these.17

Applying the same argument to precious metal mining in the British empire, it becomes necessary to look at the social factors that led to the development of the gold mining industries.

“A mine is a hole in the ground owned by a liar.” This well-known definition of mining, usually attributed to Mark Twain, captures two of the main social factors to be considered in the development of mining projects.18 First, the expertise to dig the hole in the ground, and second, the lying to convince people to give you the capital to do it. In addition to Mark Twain, this way of understanding the mining industry is supported by two more reputable sources. First, analysts within the industry, when reflecting on what makes a successful mining company, conclude that they are most successful when they are run by people who are involved in both finance and engineering – ‘financial engineers’, such as Canadian mining industry figures Pierre Lassonde and Seymour Schulich.19 Second, the dual focus on engineering and financial expertise in mining is reiterated by business historians Charles Harvey and Jon Press in their work on the history of the British global mining industry at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. Specifically, their two main works on the subject are Overseas Investment and the Professional Advance of British Metal Mining Engineers, 1851-1914 and The City and International Mining, 1870–1914, which focus on engineering and finance respectively. This essay is focusing primarily on the financial side of mining, though there is no doubt that a similar parallel investigation of the technical side of mining could also be undertaken.

london & new york

The ‘lying’ associated with getting capital to finance mining projects is usually known as promotion, and those who specialize in doing it as promoters. It entails the selling the shares of mining companies that don’t yet have a producing mine, or even a viable deposit. Due to the inherent lack of information regarding the success or failure of a particular mining project, the speculative financing of these junior mining companies is a process that differs considerably from investment in most other industries, and even from larger mining companies.

The nature of mining finance means that it primarily happens at certain stock exchanges that operate in a way that is conducive to more speculative investment, and during the late 19th century this was the case for the London stock exchange. As Harvey and Press explain,

The London share market was very open and it was possible to generate trade in a company’s shares…more easily than elsewhere…The position in London contrasted sharply with that in Germany and Paris where a much more cautious approach was taken towards dealings in international mining securities.20

A comparison of the New York and London Stock Exchanges by financial historian Ranald C. Michie describes a similar difference across the Atlantic. The high trading commissions of the NYSE made it difficult for low-value shares, such as those of many mining companies, to be traded on the exchange. This was not the case in London, and as a result the average capitalization of companies on the NYSE was five times as large as those on the LSE. Furthermore, the NYSE would refuse to list shares such as those of mining and petroleum companies because “the uncertain nature of their business was felt to make trading in their securities hazardous.”21

Exchanges typically have requirements that a company be profitable before it can be listed, or that it meet a minimum capitalization requirement. In the late 19th and early 20th century in the US, the New York stock exchange had very strict requirements of this sort, and this was done intentionally in order to only list successful companies so that more people would feel secure about investing their money through the exchange. In this way, the exchange served as a filtering system that could tell potential investors which companies were safe for investment. Most mining companies could not meet these standards, and were therefore traded unofficially on the ‘curb market’ outside the NYSE (which has since become the AMEX), and at regional exchanges were found in most major cities, especially those near mining districts.22

The exclusivity of the NYSE led to the formation of the New York Mining Stock Exchange, which complimented the NYSE by trading the mining shares that could not be traded on the larger exchange. In 1885 the mining exchange merged with the two petroleum exchanges in New York to form the Consolidated Stock and Petroleum Exchange. The new Consolidated exchange operated in direct competition with the NYSE, trading shares from many of the same companies until it finally closed in 1926.23 Mining companies and others that were not eligible for listing on the NYSE were also traded in the unregulated ‘curb market’ that originally operated on the curb outside the NYSE, before developing over time into a formal exchange that eventually became what is now the American Exchange (AMEX). In 1908, approximately 80% of the shares traded on the curb market were reported to be for mining companies, but as it became a larger, more official market independent of the NYSE, the percentage of mining shares this went down to 41% in 1914, 18% in 1920, and 4% in 1930.24 At the LSE, there were not the formal restrictions that were found at the NYSE, though there was some informal reluctance to trade smaller, speculative mining companies on the exchange. As a result there were multiple attempts through the 1860s, 70s, and 80s to form a mining exchange in London, but none of these were very successful. The London exchange was not exclusive enough to sustain the existence of a separate mining exchange.25

regional exchanges up to the TSXV present

In addition to the large central exchanges in New York and London, there were also many smaller regional exchanges located in smaller cities in England and the US. As early as the 1850s, Leeds and Sheffield listed nearly as many foreign mining companies as London, and by the 1880s this business had become concentrated in Leeds.26 In the US, the first regional exchanges were in Boston and Philadelphia, and more were established further west with the expansion of American settlement. In total more than 100 small regional exchanges were established across the US, with the largest in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles. These regional exchanges were founded to list the companies that were based in the same city as the exchange, and in cities near mining districts this often meant the formation of mining exchanges. The first San Francisco mining exchange was opened in 1862 specifically to list western mining companies. Similar exchanges were established in other cities near mining districts, such as Spokane, Denver, and Salt Lake City. In the 1930s the role of regional exchanges in the North American securities market began to change as a result of more rapid communication through telegraphs and telephones, and national regulation of securities in the US through the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1934. These changes put the US regional exchanges in more direct competition with the central exchanges in New York, which meant that the largest ones began operating more at the national level and eventually merging with each other.27

In addition to the large central exchanges in New York and London, there were also many smaller regional exchanges located in smaller cities in England and the US. As early as the 1850s, Leeds and Sheffield listed nearly as many foreign mining companies as London, and by the 1880s this business had become concentrated in Leeds.26 In the US, the first regional exchanges were in Boston and Philadelphia, and more were established further west with the expansion of American settlement. In total more than 100 small regional exchanges were established across the US, with the largest in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles. These regional exchanges were founded to list the companies that were based in the same city as the exchange, and in cities near mining districts this often meant the formation of mining exchanges. The first San Francisco mining exchange was opened in 1862 specifically to list western mining companies. Similar exchanges were established in other cities near mining districts, such as Spokane, Denver, and Salt Lake City. In the 1930s the role of regional exchanges in the North American securities market began to change as a result of more rapid communication through telegraphs and telephones, and national regulation of securities in the US through the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1934. These changes put the US regional exchanges in more direct competition with the central exchanges in New York, which meant that the largest ones began operating more at the national level and eventually merging with each other.27

Under competitive and regulatory pressures, all of the small regional exchanges in the US eventually closed down or merged into larger exchanges such as the NYSE that were not as open to mining finance. However, this didn’t mean the disappearance of speculative equity markets for junior mining companies in North America. Various Canadian stock exchanges were, and have continued to be, open to mining speculation. In the 1890s two small mining exchanges formed in Toronto in response to the demand for speculative mining investment during the gold rush in British Columbia. In 1898 the two exchanges merged to form the Standard Stock and Mining Exchange (TSSME).28 During the first three decades of the 20th century, this exchange grew quickly. Starting with the first major gold and silver rushes in the Canadian Shield from 1903 to 1912, the exchange turned Toronto into a center for mining finance.29 This trajectory resembled the rise of regional exchanges in mining districts in the US. Just as the US regional exchanges had come under pressure to merge in the 1930s, so too did the Standard Stock and Mining Exchange in Toronto. The crash of 1929 had brought scandal and criminal charges for five prominent brokers on the TSSME, whereas the larger, better regulated Toronto Stock Exchange emerged from the crash unscathed. As a result, the two exchanges merged in 1934.30

In keeping with the previously described tensions between the speculation of mining finance and the more conservative investment patterns of other business sectors, the Toronto Stock Exchange began introducing “more stringent regulations and speculations” following the merger with the mining exchange.31 It was also at this time that Toronto succeeded Montreal as the national center of Canadian finance, giving it a similar role as New York in the US. However, unlike New York, in addition to being a national center of finance Toronto was also a financial center that had grown out of a mining district. Therefore, despite the stricter regulation of speculation following the merger with the Standard Stock and Mining Exchange, the Toronto Stock Exchange continued to be relatively open to mining stocks. However, as time passed pressure mounted for the TSX to reign in the speculative trading associated with junior mining companies. In 1951 the SEC in the US accused the brokers on the TSX of “swindling Americans out of $52 million annually” and in 1964 the situation exploded with the Windfall scandal, in which the rapid rise and then crash of a mining stock resulted from share price manipulations and faked core samples.32

In the backlash following the Winfall scandal, the Ontario government imposed heavy regulations on mining speculation. Unable to do their business in a regulated setting, promoters and brokers of junior mining companies left Toronto en masse and began operating in Vancouver instead. This was the beginning of the reign of the Vancouver Stock Exchange as the center of speculative mining investment in Canada, world renown for its lack of regulation and transparency.33 The VSX maintained this status until the end of the 20th century when another major mining speculation scandal again shifted the landscape of equity markets in Canada. In 1997 the Bre-X fraud involving fake gold deposits and a hugely inflated share prices continued until the truth was revealed and it all crashed. The fallout from this massive scandal undermined confidence in all Canadian mining equity markets, and resulted in the merger of all of the Canadian junior mining exchanges. Vancouver was the largest, but there was also the Calgary exchange, and the Montreal-based Canadian Exchange. In 2000, junior mining once again returned to Toronto through the formation of the TSX Venture Exchange, which now operates as a subsidiary of the TSX. This history of shifting mining finance demonstrates that it has been a hot potato that has been passed around the world. Most exchanges have not been willing to hold it, and holding it long enough has eventually meant getting burned by scandal and illegitimacy.

canadian exceptionalism

The kinds of regulations that were originally used to instill investor confidence on the NYSE are still prevalent on most exchanges today, and they make listing difficult if not impossible for most junior mining companies. There are very few TSXV-listed mining companies that are cross-listed on American exchanges. This can be explained by the lack of a comparable speculative or venture exchange in the US other than unregulated OTC (Over The Counter) systems such as Pink Sheets. All of the American public exchanges are too regulated for junior mining companies. This argument for the uniqueness of the TSXV can be expanded to the global level based on the paper “The Canadian Public Venture Capital Market”, in which Cecile Carpentier and Jean-Marc Suret claim that the TSXV is the only public venture exchange in the world. They explain that it is the only exchange that specializes in micro-capitalization companies, and note that many of these companies are resource-based, which includes mining.34

The TSXV lists most junior mining companies, though some of them are listed on the TSX. Overall, of the 1408 mining companies currently listed on both exchanges, 25% of them on the TSX, and 75% are on the TSXV. Based on a rough estimate of senior, intermediate and junior demarcations among all of the mining companies on the TSX and TSXV, the distributions of companies and capital among the sectors is as follows: 10 seniors are less than 1% of the companies and 60% of the QMV (quoted market value); 50 intermediates are 3.5% of the companies and 25% of the QMV, and 1348 juniors are 95.5% of the companies and 15% of the QMV.35 This skewed distribution of capital among companies is a defining feature of the Canadian mining industry, and Canadian equity markets in general. A slightly different way of describing the situation would be to say that there are a very large number of small junior mining companies. This is especially significant because it defines the whole Canadian economy, and for this reason one economist claimed that “…it is not unfair to say that an unusually large number of publicly traded companies may truly be regarded as an example of ‘Canadian exceptionalism.’”36 This exceptionalism demonstrates both the importance of mining in the Canadian economy, and the importance of the Canadian economy to the global mining industry. The TSX and TSXV are well aware of this situation, and promote themselves to investors and the mining industry as “global leaders in providing access to capital for growth-oriented mining companies.”37

canada, & how the apple doesn’t fall far from its 19th-century british colonial tree

By virtue of its fundamental uncertainties, industrial mining has always depended on a form of speculative financing that is only possible under certain institutional and regulatory conditions. These conditions were first met in the relatively laissez-faire capital markets of London, as well as in the completely laissez-faire regional exchanges that emerged in most mining districts in North America. However, this speculative financing could not institutionally co-exist with the more regulated, predictable exchange conditions required for the financing of non-extractive industrial production (as epitomized by the NYSE). Over time, securities regulations, stock market consolidation, and competitive pressures to provide more stable exchange conditions, led to the disappearance of most stock exchanges that could support the speculative conditions required for exploratory mining capital. By the latter half of the 20th century, the Vancouver and Calgary stock exchanges were two of the last remaining vestiges in North America of this earlier form of financial institution. In recent years, these markets have been consolidated into the TSXV in Toronto, but its exceptional role in financial supporting the mining industry continues. As the only stock exchange of its kind in the world, the TSXV provides unique conditions for the financing the exploratory work of the global mining industry.

We have established that precious metals mining in Canada, and the social patterns of and legal justifications for dispossession that accompany it, are tied fundamentally to an overwhelming historical process of land-grabbing European expansionism that has plagued the world since the mid-fifteenth century. We’ve established as well that this process of imperialism was tied up with the development of the global capitalist system that we know today– specifically, tracing the lineage of speculative market structures, from nineteenth-century London financial markets to the particularly lax regulations for mining companies trading on the Toronto Stock Exchange today. Canada, then, in both its ongoing domestic mining policy and its dominant role in the global extractive industry, is performing according to the social and economic rules set out for it by a particular form of British imperial capital. •

a version of this essay was presented at Study in Action 2010, Montreal

notes

1. Harold Innis, “Introduction,” in Elwood S. Moore, American Influence in Canadian Mining, (TO: University of Toronto Press, 1941), v.

2. R.T. Naylor,Canada in the European Age, 1453-1919 (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1987), 3-19.

3. Ibid., 47.

4. Ibid., 417.

5. Ibid., 238.

6. Edward D. Castillo, “Short Overview of California Indian History,” California Native American Heritage Commission, http://www.nahc.ca.gov/califindian.html (accessed February 22, 2010); Douglas Fetherling, The Gold Crusades: A Social History of Gold Rushes, 1849-1929 (TO: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 11-41; see also Robert F. Heizer and Alan J. Almquist, The Other Californians: Prejudice and Discrimination Under Spain, Mexico, and the United States to 1920 (Berkeley and LA: University of California Press, 1971), 23-64.

7. Roger Moody, Rocks and Hard Places: The Globalization of Mining (Halifax: Fernwood, 2007), 46.

8. Adele Perry, On the Edge of Empire: Gender, Race, and the Making of British Columbia, 1849-1871 (TO: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 9-10.

9. Fetherling, The Gold Crusades, 67-81.

10. Ibid., 73-74.

11. See Barry J Barton, Canadian Law of Mining (Calgary: Canadian Institute of Resources Law, 1993).

12. Karen Campbell, “Undermining Our Future: How Mining’s Privileged Access to Land Harms People and the Environment – A Discussion on the Need to Reform Mineral Tenure Law In Canada,” West Coast Environmental Law, http://wcel.org/sites/default/files/publications/Undermining%20Our%20Future%20-%20A%20Discussion%20Paper%20on%20the%20Need%20to%20Reform%20Mineral%20Tenure%20Law%20in%20Canada.pdf (accessed February 5, 2010).

13. E.G. Haliburton, “The Past and the Future of Nova Scotia,” Nova Scotia in 1862 [microform]: papers relating to the two great exhibitions in London of that year, http://www.archive.org/stream/cihm_23167/cihm_23167_djvu.txt (accessed 25 February, 2010).

14. Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert, “Exhausting the Sierra Madre: Long-Term Trends in the Environmental Impacts of Mining in Mexico” (paper presented at Rethinking Extractive Industry. Regulation, Dispossession, and Emerging Claims –York University, March 5-7, 2009), 3-4.

15. Daniel Cornford, “‘We All Live More like Brutes than Humans’: Labor and Capital in the Gold Rush,” California History 77, no.4 (Winter, 1998/1999), http://www.jstor.org/stable/25462509 (Accessed August 12, 2010).

16. Mira Wilkins, The history of foreign investment in the United States, 1914-1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 81-82, 557-558, 754-755.

17. Paul David and Gavin Wright, “Increasing Returns and the Genesis of American Resource Abundance,” Industrial and Corporate Change 6, no. 2 (1997): 204.

18. Barbara Schmidt, “Miners,” Mark Twain quotations, http://www.twainquotes.com/Miner.html (accessed July 18, 2009).

19. John Katz and Frank Holmes, The Goldwatcher: Demystifying Gold Investing (Chichester: Wiley & Sons, 2008), 234-235.

20. Charles Harvey and Jon Press, “The City and International Mining, 1870–1914,” Business History 32, no. 3 (1990): 114.

21. Ranald C. Michie, “The London and New York Stock Exchanges, 1850-1914,” The Journal of Economic History 46, no. 1 (1986), http://www.jstor.org/stable/2121273 (accessed July 25, 2009).

22. Lance E. Davis and Robert J. Cull, International capital markets and American economic growth, 1820-1914 , (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 72-77.

23. William O. Brown Jr, J. Harold Mulherin and Marc D. Weidenmier, “Competing with the New York Stock Exchange,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (2008).

24. Mary O’Sullivan, “The Expansion of the U.S. Stock Market, 1885–1930: Historical Facts and Theoretical Fashions,” Enterprise & Society 8, no. 3 (2007): 505.

25. Roger Burt, “The London Mining Exchange 1850-1900,” Business History 14, no. 2 (1972).

26. Lance E. Davis and Larry Neal, “The changing roles of regional stock exchanges: an international comparison,” (paper presented at Social Science History Association meeting, Chicago, IL November 19, 1998), 19.

27. Tom Arnold et al., “Merging Markets,” The Journal of Finance 54, no. 3 (1999): 1085.

28. E.P. Neufeld, The Financial System of Canada: Its Growth and Development (Toronto: Macmillan, 1972), 478.

29. Donald P. Kerr, “Metropolitan Dominance in Canada,” in Canada: A geographical interpretation, ed. John Warkentin (Methuen, 1970), 541.

30. Neufeld, The Financial System in Canada, 497.

31. Kerr, Metropolitan Dominance, 541-543.

32. David Cruise and Alison Griffiths, Fleecing the Lamb: the Inside Story of the Vancouver Stock Exchange (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1987), 72-75.

33. Ibid, 82-85.

34.Cécile Carpentier and Jean-Marc Suret, “The Canadian Public Venture Capital Market,” CIRANO Working Papers 2009s-08 (2009).

35. TMX Money, “Mining,” TMX Sectors and Investment Products, http://www.tmxmoney.com/en/sector_profiles/mining.html (accessed July 01, 2009).

36. Christopher Nicholls, “The Characteristics of Canada’s Capital Markets and the Illustrative Case of Canada’s Legislative Regulatory Response to Sarbanes-Oxley,” Research Study Commissioned by the Task Force to Modernize Securities Legislation in Canada (2006).

37. Toronto Stock Exchange, “Unearth a World of Mining Capital” (from the Prospectors and Developers Association Conference, March 1-4 2009).