the role of temporary migrant workers in canadian food production

kerri westlake

I will be discussing policies which grant temporary work permits to people living outside of Canada, known as guest worker programs. Although guest worker programs provide permits for many sectors, I will be focusing on agriculture.

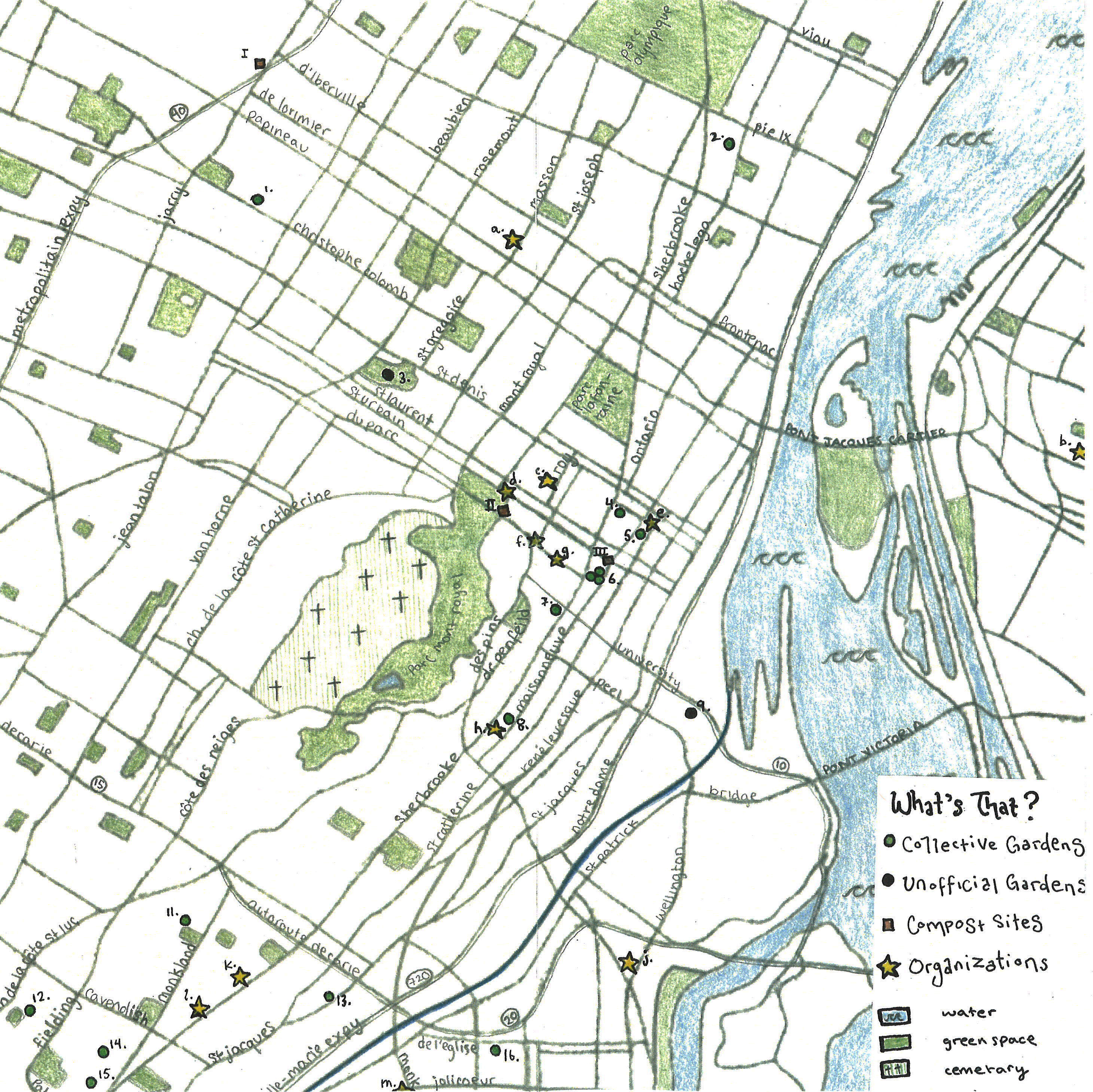

I started this research for the McGill Food Systems Project, in response to their request for criteria to help the administration choose between food providers. The goal of the project is to embed environmental and social concerns within the university’s food purchasing policies, which to date have been focused primarily on price and quality. In building the criteria we tried to be cautious of the criticism of environmentalism as a historically white middle class movement that often fails to incorporate social concerns in discussions of sustainability. Examining human health and working conditions was one of the ways we tried to address this issue. I will be expanding on this section of the project, which is actually a work-in-progress. Specifically, I’ll be expanding on the SAWP and TFWP as two increasingly important sources of labour in Canadian agriculture.

I want to begin by mentioning that there are ways in which my race, class, and cis- gender privilege inevitably informs my research both in ways I have tried to be mindful of and in ways that may be invisible to me. Additionally, the scope of sources I consulted was restricted by my English and limited French language skills. This is most evident in what I see as the greatest flaw in my research- the lack of formal incorporation of primary interviews. That said, I have had informal discussions with industry representatives, farmers, workers, and support workers. So thanks so much to those shared their stories and ideas.

Guest worker programs are racist immigration policies which create differential rights for those considered ‘temporary’ compared to those considered ‘permanent’. The distinction between permanent and temporary is based on a gendered and racialized definition of ‘skills’ which is legitimized by the discourse of citizenship. Guest worker programs are based on the exploitation of temporary non-citizens to protect the economic privilege of permanent citizens. This presentation will discuss the ways in which the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program (SAWP) and the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) bolster the economic success of Canada’s agricultural industry in a globalizing economy by restricting the rights and voices of temporary migrant workers.

The context in which my research emerged- that is, in the quest for ‘sustainable’ food – is one where much of the current literature calls for increasing local consumption. Often implicit in the argument for local food is a particular image of what it means to eat locally. This image has been taken up in branding and marketing tools, which conjure images of rolling pastures dotted with quaint houses inhabited by a tired but happy white family working in harmony with their domesticated animals to offer up sustenance to urban consumers. Such romantic visions of the Canadian family farm are prevalent in advertising and packaging and underlie much of the current push for local food.

But, not only are such romanticizations premised on the erasure of agriculture’s historic reliance on a precarious and marginalized workforce, such as the use of British orphans in the early 1900s, and interned Japanese Canadians and German POWs during the world wars, but today they are more inaccurate than ever.1

trends in canadian agriculture

Similar to global trends, Canadian agriculture has been characterized by expansion and consolidation. In the past few decades the number of farms has declined, while average farm size has grown, as has corporate control of these farms.2 The percentage of children from farming families who pursue careers in agriculture is also rapidly declining.3

These trends have been in part caused by trade liberalization policies wherein, in order to remain economically viable in a globalizing market, farms must grow larger and larger to gain cost benefits that accompany economies of scale.4 In North America, these policies have led to divestment in small scale agriculture, the loss of former export markets, and artificial depression of commodity prices as a result of subsidies. One important consequence is a race to the bottom in terms of production costs, including labour costs.

The trends have meant growing demand for so called “low skilled” wage labour, while the destabilization of local or subsistence economies has created a surplus of dislocated workers. While there has always been a discernable link between the Canadian economy, agriculture and immigration policy, it is particularly tangible in this context. Since the 1960s, the government and agricultural industry have been claiming this labour shortage with increased force.

SAWP and the creation of a ‘reliable’ workforce

Enter the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program. Initiated in 1966 in an agreement between the Canadian and Jamaican governments, SAWP grants temporary permits to low skilled workers in agriculture if employers, in accordance with the Canadians First policy, could prove that they could not recruit Canadian workers.5 It is important to note that the low skill category is based on the devaluation of manual work, and does not accurately reflect the importance of what these workers provide. (Indeed, the process of ‘naming’ – choosing which employees return to work in subsequent years – is so beneficial to employers because of the increased skills a returning employee can offer. Employers can also request workers with specific skills such as experience operating complex machinery.6)

Prior to this agreement, labour shortage demands had been largely met with permanent immigration recruitment programs that were highly regulated as to who may or may not enter. Temporary work, agricultural and otherwise, had been an informal phenomenon wherein migrants sought seasonal work in Canada with the expectation of returning to their place of origin.

The novel emergence of state sanctioned temporary labour programs has become a strategy for ensuring Canada’s successful competition in a globalizing economy. A reliable source of cheap labour was and is essential to encourage and maintain capital investment.7 But because agriculture is among the most hazardous and low paying sectors it is difficult to find employees. Additionally, the extent to which labour rights legislation applies to agricultural work is based on the relic of the family farm I discussed earlier, where rising costs associated with increased rights were not considered possible.8 As a result, to use Quebec as an example, farm workers’ weekly minimum of one day of rest can be postponed, and they are not paid overtime.9 These conditions combine to create a sector in which, as government and industry representatives frankly admit, most Canadians will not work.10

Where Canadian residents or citizens are employed, they are most often poor or recent immigrants, and are often characterized as “unreliable” by their employers. For example, an article in Canadian Poultry Magazine states that a chicken catching company had previously “…had so much trouble finding catchers that we had to accept such unacceptable behaviour [as taking illicit drugs on the job]” but that “a major part of the solution came… when [we] started hiring guest workers from Guatemala…. Workers from Quebec know that they can be replaced”.11 The differentiation between reliable and unreliable workers is often conflated with race, gender, ethnicity, and/or nationality, but as scholar Nandita Sharma argues, “what allows migrant workers to be used as a cheap and largely unprotected form of labour power are not any inherent qualities of the people so categorized but state regulations that render them powerless”.12 It is by facilitating this conflation that the SAWP and TFWP act to perpetuate racist stereotypes as well as to create severe disincentives for workers to be anything but reliable.

SAWP, which has been expanded since 1966, is a program jointly overseen by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC), and the consulate of the sending country.13 While Canadian employers dictate the demand for workers and CIC ultimately grants work permits, the sending country is responsible for worker recruitment and all associated costs. Sending countries compete with each other to provide the most reliable workers at the quickest response time, as the remittances sent back now contribute significantly to these economies.14 These same agents have the role of advocating for workers’ rights but the two conflicting incentives limits worker representation in the event of a complaint and in annual negotiations. Unequal representation is one of many ways in which employers are granted power by this program.

Employers also have full discretion as to which employees return to their farm. Through the process know as naming, employers can request certain workers back by name, in some cases for up to 20 consecutive years.15 Likewise, employers are granted the discretion to fire an employee for “any significant reason”; the North South Institute has reported reasons such as falling ill, questioning wages, and refusing unsafe work.16 Since a worker’s permit is tied to a specific employer, to be fired is to lose one’s status in the country. This is important because the threat of repatriation combined with the prospect of not being ‘named’ in the coming seasons engenders fear of speaking out or detesting sub-standard conditions. But, as they are currently set up, the SAWP and TFWP rely on worker complaints to determine whether employers are abiding by the program rules or provincial labour standards; the Commission des normes du travail (CNT) and the Commission de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CSST) will only perform workplace inspections upon receipt of a complaint.17

In addition to restricting workers’ voices, SAWP is designed such that its workers have fewer rights than their Canadian counterparts. That one’s status is tied to a specific employer means that workers within this so called “labour mobility program” do not have the mobility to freely sell their labour as Canadians do. Also, while Employment Insurance (EI) is deducted off of the paycheques of SAWP employees, their loss of status and repatriation upon losing or finishing a job contract makes it practically impossible to claim EI payments. Similarly, while all foreign workers in Canada in theory have the same right as citizens to contest termination before the law, repatriation again means that this is impossible. What underlies all of these injustices is the threat of repatriation and the fear and silence it engenders.

Many live on the property of their employers, who have full discretion to impose safety, discipline and property rules, often further limiting worker mobility. There have been a number of documented cases wherein employers withheld workers’ personal documents, or refused to grant worker requests to be taken to medical facilities.18 The availability of documentation in Spanish, the first language of many workers, is limited.

In 1987, true to trade and econ lib trends, the HRSDC relinquished administrative control of the SAWP to Foreign Agricultural Resource Management Services (FARMS). FARMS is a non-profit, member (i.e. employer) funded and driven company. Simultaneously the cap on how many permits were granted was removed, and the number of SAWP workers increased 15 fold the next year. The move also increases employer representation in annual negotiations, particularly unjust considering the inability of SAWP workers to bargain collectively. Collective bargaining rights allocated to the majority of Canadian citizens are denied to agricultural workers in Ontario and Alberta. In Quebec, while not explicitly forbidden, Article 21 of The Quebec Labour Code requires that there are 3 ordinary and continuous employees- obviously a problem for those employed in seasonal or otherwise precarious work.

increasing precarity under the temporary foreign worker program

Despite the clear position of power that employers are already in, they continue to demand a more flexible, less regulated workforce. These demands were met in 2003 with the initiation of both the Live-In Caregiver program, which I unfortunately don’t have time to talk about, as well as the TFWP, an expanded and deregulated program modeled on SAWP.

The TFWP expanded employment possibilities to new sectors and is organized outside of bilateral agreements, meaning that there are no annual negotiations with sending governments and that workers can be recruited from anywhere in the world.19 This means that if one workforce begins to demand rights, employers can easily hire a completely different set of workers. As one worker observed, this effect can already be seen: “they see that Mexicans are showing their claws and want to defend their rights, so now they prefer Guatemalans because they are more silent”.20

While these programs are purportedly beneficial for economic empowerment and livelihoods of people in so-called developing countries, and are thus used to bolster the image of Canada as benevolent, they are in effect akin to slavery. As Eugenie Depatie- Pelletier argues, the conditions set up by the SAWP and TFWP are in breach of the UN Supplementary Convention of the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery, which Canada ratified in 1957. According to this agreement, the “condition or status of a tenant who is by law, custom or agreement bound to live on land belonging to another person and to render some determinate service to such another person, whether for reward or not, and is not free to change his [sic] status” should be abolished at any cost.21 SAWP and TFWP workers are both required to live on their employer’s property, as well as prohibited from seeking permanent status once in Canada.

That SAWP and TFWP workers’ permits are tied to one employer goes against the right to liberty and security of the person and freedom of association in Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.22 These rights restrictions stand in stark contrast to those afforded to so called “high skilled” workers or temporary workers coming from wealthy predominantly white countries. Both high skilled workers with a temporary work permit and low skilled workers from predominantly European and Commonwealth countries are allowed to seek permanent status in Canada and neither are restricted to one employer nor repatriated upon termination of employment.23

It is the conditions which create a precarious workforce that ensure the success of the industries in which these workers participate. In the past decade, Canada has become a net exporter of six out of eight crops where SAWP workers are hired (apples, tomatoes, tobacco, cucumbers, peaches, cherries, ginseng, and greenhouse tomatoes.24 This workforce is becoming what Sharma calls “permanently temporary”, as more similar work programs are implemented and the amount of workers participating in them is overtaking the number of citizens/residents in some sectors.25 For example, in horticulture TFWs now represent 18% percent of the total workforce and 53% of the workforce in SAWP employing sectors.26 People destined to enter the workforce with permanent status have shifted from 57% in 1973 to 30% 20 years later. The remaining 70% were workers entering with temporary status.27

how the discourse of citizenship legitmizes exploitation

The importance of these workers to the Canadian economy is clearly at odds with their temporary, non citizen status but it is precisely their non-citizen status which allows for the legitimization of differential rights that are essential to their economic value. And, as Sharma argues, these unequal rights are naturalized by discourses of citizenship.

For example, in a 1971 discussion in the House of Commons, when asked whether unemployed citizens rather than “offshore” workers could be encouraged to work in agriculture by increasing social benefits, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau replied: “No… the government will not commandeer the work force. The whole political philosophy of the government is based on freedom of choice for citizens to work where they want”.28 It is clear that freedom to choose where one wants to work is a right reserved for citizens but also, that such a statement is not openly acknowledged as contradictory, is evidence of how citizenship naturalizes the existence of two sets of rights.

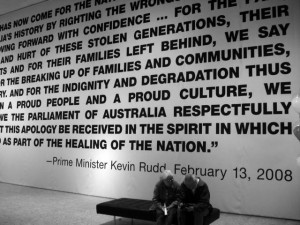

Of course, differential rights for citizens and non-citizens have been constant throughout Canadian history. The definition of citizenship began as explicitly racialized, preferencing immigrants who would not, to quote former Prime Minister Mackenzie King in 1947, “…fundamental[ly] alter the character of our population”.29 They remained so until the era of multiculturalism in the 1960s. This is popularly proclaimed as the time when Canada moved from a racist state to an inclusive one but, as evidenced by the SAWP and TFWP as well as the issues my co-panelist have discussed, terms of citizenship are still racist.

Throughout the presentation, I have talked a lot about the ways in which Canadian immigration policies restrict the rights and voices of temporary migrant workers, but I also want to make it clear that these policies by no means render these workers without agency. Nor have these conditions been passively accepted by workers. As long as there have been differential rights allocated to temp workers there has been resistance.

I just want to end by saying that the process of developing criteria for McGill’s administration has been a frustrating one that has further solidified in my mind the comments made by last nights’ panelists. To affect change, it is necessary to target capitalism as the root cause of these issues. •

a version of this essay was presented at Study in Action 2010, Montreal

1. Preibisch, KL. 2007. Local produce, foreign labor: Labor mobility programs and global trade competitiveness in Canada. Rural sociology 72 (3):418-449.

2. Ibid.

3. Statistics Canada. 2001. 2001 Census of Agriculture. Government of Canada. Ottawa.

4. Sharma, N. 2008. On Being Not Canadian: The Social Organization of “Migrant Workers” in Canada. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue canadienne de sociologie 38 (4):415-439.

5. Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. 2009. Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program HRSDC Publication Services. [Accessed February 2010]. Available from http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/workplaceskills/foreign_workers/ei_tfw/sawp_tfw.shtml.

6. Preibisch, 2007.

7. Sharma, 2008

8. Choudry, A, J Hanley, S Jordan, E Shragge, and M Stiegman. 2009. Fight Back: Workplace Justice for Immigrants. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing Co., Ltd.

9. Gouvernement du Québec. 2001. An Act Respecting Labour Standards. edited by Commission des normes du travail. Quebec.

10. Sharma 2008.

11. Dumont, A. 2010. A Tough Job: Farmers can help make it easier. Canadian Poultry Magazine.

12. Sharma 2008, 425.

13. The program now includes Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Antigua, Dominica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Monserrat and Mexico.

14. Brem, M. 2006. Migrant Workers in Canada: A review of the Canadian Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program. edited by L. Ross. Ottawa: North South Institute.

15. The threat of refusing to name the family members of a given worker has also been reported; Brem 2006.

16. Ibid.

17. Personal interview with representatives of the CNT and the CSST, November, 2009.

18. United Food and Commercial Workers Union of Canada. 2007. The Status of Migrant Farm Workers in Canada 2006-2007. Toronto.

19. Additionally, unlike SAWP employees, TFWP workers pay for there accommodation, have no minimum requirement for hours worked per contract, and can stay for up to 2 years; Canada, Human Resources and Skills Development. Temporary Foreign Worker Program 2010 [Accessed March 2010]. Available from http://www.rhdcc-hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/workplaceskills/foreign_workers/index.shtml.

20. Choudry et al 2009, 69.

21. Depatie-Pelletier, E. 2008. Under legal practices similar to slavery according to the UN Convention: Canada’s “non white”“temporary” foreign workers in “low-skilled” occupations. In 10th National Metropolis Conference. Halifax.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Brem 2006; Preibisch 2008.

25. Sharma, 2008.

26. Brem, 2006.

27. Sharma, 2008.

28. Ibid, 433.

29. King, William Lyon Mackenzie. 1947. Canada’s Postwar Immigration Policy. Paper read at House of Commons Debates, at Ottawa.