simone lucas

(((Simone is a senior at McGill University where she is a member of the QPIRG board of directors and is writing an Honours thesis on site-specific feminist performance art.)))

The papers that Simone and Eve present here are based on a co-authored paper they gave at Study in Action 2012, Montreal.

Their collaboration began with exchanges about women writers. Recently, their discussions grew into a shared project on pain and disability as lived experiences and as subjects of study. Their joint research focuses on the social construction of pain and on the intellectual and technical means used to describe and evaluate it.

introduction

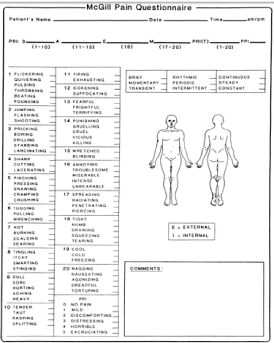

In her memoire “Inside Chronic Pain”, Lous Heshusius shares her struggle to articulate the persistent pain she has lived with for over a decade. She experiences pain that is impossible to put into words, and that is alien to others. Conveying pain to her doctors is a particular challenge: “I try to speak to doctors about the severity of my pain. My words float strangely in the air. As I pronounce them, I myself become a spectator. As soon as I begin to speak, I am no longer there.”(15) For millions of people living with chronic conditions around the world, all-consuming pain is a daily occurrence, and leads to social isolation. People living with chronic pain confront reactions of disbelief, and find themselves convincing friends, health professionals and strangers that their pain is real, present and disabling despite the fact that it is invisible. Yet often language fails. The “McGill Pain Questionnaire” (MPQ), a questionnaire developed by Ronal Melzak for use in clinical settings, attempts to enable the expression of pain by providing a list of seventy-eight words. The questionnaire aims to present health professionals with a fuller picture of the characteristics and intensities of a painful experience. In this paper, I will examine the MPQ as a communication and measurement tool that mediates patient-doctor interactions. I argue that though it may help patients find words to describe their pain, it objectifies their experiences as scientific data and enables the continued neglect, fear and stigmatization of people living with pain.

the pain scale

Doctors and researchers have devised a number of tools to not only understand a patient’s pain, but also to measure, quantify, chart, track and abstract it. An example of one such tool is the pain scale, which asks you to rate your pain. Different institutions use different vocabulary to describe the numerical range of pain intensities: from 0-10, from mild to excruciating, or from “no pain” to “worst pain imaginable”. For people living with persistent severe pain, these scales are used to track their condition over time. But can pain be reduced to a single number? And what if my “worst pain imaginable” is only your #3? Eula Biss devoted a poem to the experience of measuring her pain. She wrote: “The pain scale measures only the intensity of pain, not the duration. This may be its greatest flaw. A measure of pain, I believe, requires at least two dimensions. The suffering of Hell is terrifying not because of any specific torture but because it is eternal.” (30)

Fig 1: Pain Scale

In the mid-1980s, Dr. Ronald Melzack, a psychologist at McGill University, realized the failings of the pain scale. He conceived of another way to understand pain, not as a one-dimensional scale, but as a noun with qualifying adjectives. He reasoned that pain does not only vary in intensity, from “mild” to “extreme”, but also in temperature, pressure, pulse, spatiality, heat, dullness, and even in psychological qualities such as tension, fear, and punishment. Based on his initial observation of the pain scale, Dr. Melzack, along with Dr. Torgerson and other colleagues, began the development of the MPQ. The questionnaire is a form given to patients to fill out prior to an initial assessment at a pain clinic or specialist office. It lists a total of seventy-eight words separated into twenty unnamed groupings. Patients are told to make a mark next to the words that describe their pain. They can only choose one word per category. This form is meant to help patients find the precise words to communicate their pain to doctors.

the questionnaire

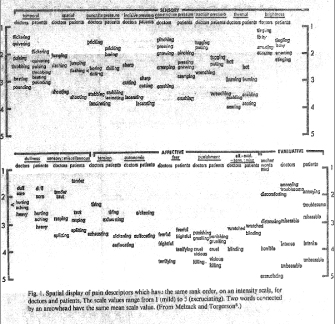

In his paper, “The McGill Pain Questionnaire,” Melzak describes the processes and methodologies used to develop the form. A close reading of this paper will show that patients were only marginally involved in the process of explaining their own use of language to express pain. While the study made use of patient’s words, it was empiricists who assigned meanings and numerical values. Melzack and Torgerson began the development of the questionnaire by gathering a list of forty-four words describing pain from a 1939 psychology textbook (40). They added to this list other words gathered from “clinical literature and from descriptions given by patients at hospital clinics.” (41) They arrived at a list of one-hundred-and-two words, and found that it “was a meaningless jumble.” (41) And so, they had physicians and university graduates classify them “into small groups describing distinctly different qualities of pain.” (41) The words were then organized into three major classes and sixteen subclasses. The three classes were: 1) the sensory class, which includes temporal, spatial, pressure, thermal, brightness, dullness, and other properties of pain; 2) the affective class, which describes psychological effects, such as fear, horror, or tolerance levels; 3) and the evaluative class, which is similar to a pain scale in describing the subjective intensity of the pain from mild to excruciating. These sets of sensory, affective, and evaluative classes, each containing subclasses, are compiled within the questionnaire to be presented to patients.

Following the organization of these pain descriptors, Melzak and Togerson proceeded to assign a numerical value to each word in the questionnaire. Based on a ranking system, they ranked words in each class along a numerical scale. For instance, within the “incisive pressure” subclass, the words were rated in the following order, from slightest to worst pain: 1) sharp, 2) cutting, 3) lacerating. They then devised various numerical units associated with these rankings and with the overall questionnaire: 1) The pain rating index, which assigns a numerical value to each word 2) the number of words chosen by the patient, and 3) the present pain intensity, the overall intensity rating at the time of the questionnaire, from a level of 0-no pain, to 5-excruciating. The questionnaire is meant to help doctors understand what kind of pain the patient is having, and to assign a numerical value to that pain.

When patients fill out the questionnaire, they are unaware of the various categories to which words refer or of their numerical values. Because the words on the questionnaire are adjectives and not numbers, patients remain under the impression that they are only describing their pain, not rating its numerical intensity. How could they guess that “gnawing” would indicate less pain than “crushing,” that “lacerating” would be worse than “boring,” or that psychological qualifiers—such as vicious, killing, and terrifying—would be rated higher than sensory adjectives? In the original development of the questionnaire, patients were uninvolved in the interpretation and organization of words into various subclasses with numerical rankings. When put into practice, the questionnaire similarly excludes patients’ understanding of pain while also obfuscating the way their answers will be understood by doctors. Doctors may execute medical decisions based on the numerical values assigned to words while bypassing their patients’ personal account. The “McGill Pain Questionnaire” supplements the patient’s subjective narrative with an empirical measurement of pain.

the social meaning of pain

Presumably, the “McGill Pain Questionnaire” was designed to give patients a voice to describe their suffering. Yet there is more that separates patients and doctors than a loss for words. Relationships between people living with persistent pain and their doctors exist within a social sphere of stigma, fear, and systematic oppression of the disabled. Feminist disability theorist Susan Wendell argues that our society idealizes the productive, functional body. This idealization leads to the marginalization and fear of people with disabilities. Pain is particularly feared, as it can remind us of the possibility of our own physical pain. We might even blame the person for their pain: “I may tell myself that she could have avoided it, in order to go on believing that I can avoid it.” (343) Because we cannot confront the imperfection of our own bodies, and the possibility that we too can be incapacitated through pain, we treat the disabled person as fundamentally other. Wendell continues to argue that in a medical setting, doctors fear their inability to fix the body and return it to standard functionality. They are often more focused on curing physical ailments than on understanding long-term illness and disability. Therefore, it is not only the fundamental inexpressibility and unsharable nature of pain that sets apart people with chronic pain, but also the fears they inspire in society at large.

Though the MPQ may help patients find words to describe pain in certain instances, and though it may provide reproducible numbers for clinical trials, it circumscribes the patient-doctor relationship to the goal of measuring and curing disease. It translates the patients’ symptoms into nouns with qualifying adjectives, into fixed measures and descriptors of pain. The questionnaire does not give people living with pain the space to tell their story, to describe the unique form and shape their pain can take depending on the time of day, and the many ways it affects their lives.

Despite the presence of this test in clinical settings, doctors regularly dismiss chronic pain patients. Lous Heshusius describes numerous harrowing experiences of being avoided or mistreated. Though she noted her suicidal depression on multiple questionnaires, most doctors avoided addressing it while including this information in their reports, and sharing it with other doctors. The questionnaire prescribes a fixed framework of words and values, yet does not allow for patients to explain what their pain means to them or give doctors the specific information about their condition. The questionnaire desocializes words. It takes words out of the context of the patient’s life and social situation, and transforms them into objective, numerical data for the empiricist. In a culture where people with chronic pain are routinely dismissed by doctors and socially stigmatized, this questionnaire gives answers in the form of hard data without urging doctors to examine their own prejudices towards chronic pain, or to truly consider the person in front of them.

bibliography

Biss, Eula. “The Pain Scale.” Harper’s Magazine. (June 2005): 25-30.

Heshusius, Lous. Inside Chronic Pain: An Intimate and Critical Account. Ithaca: ILR Press & Cornell University Press, 2009.

Melzack, Ronald, & Patrick D. Wall. The Challenge of Pain. 1982. Updated 2nd edition. London & New York: Penguin Group, 1996.

Melzack, Ronald. “The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major Properties and Scoring Methods.” Pain 1 (1975): 277-299.

Melzack, Ronald. “The McGill Pain Questionnaire.” In Pain Measurement and Assessment. Ed. Ronald Melzack. New York: Ravel Press, 1983.

Wendell, Susan. “Toward a Feminist Theory of Disability.” In The Disability Studies Reader. 3rd ed. Ed. Lennard J. Davis. New York & London: Routledge, 1997.

Young, Allen. “The Anthropologies of Illness and Sickness.” Annual Review of Anthropology. 11 (1982): 257-85.